Last week marked the 10th anniversary of what has become known as the “Miracle on the Hudson.” It was on January 15, 2009 that Captain Chesley “Sully” Sullenberger landed US Airways Flight 1549 in the Hudson River off Midtown Manhattan. Sullenberger’s memoir, Highest Duty: My Search for What Really Matters was adapted into the feature film Sully: Miracle on the Hudson directed by Clint Eastwood in 2016 with Tom Hanks in the title role.

Eastwood’s film explores the many levels of fascination with this extraordinary event: What was it like to be a passenger on the plane? What was it like to be the air traffic controller talking to the pilots? Or, what was it like to be participating in the rescue from a boat on the river? But of course, the biggest fascination is about what was going in Sully’s head during this event. How did he even think to land a jet aircraft on the Hudson River?

An unexpected event of this magnitude would be unlikely in most people’s lives, yet, less consequential circumstances that require quick thinking and dynamic responses for resolution happen all the time. And I wonder, what can we learn from Sully to better prepare ourselves to successfully respond to our own dynamic situations?

Frank Barrett talks about this in his book Yes to the Mess. He calls responses like Sully’s dynamic capabilities, and says that they can be developed as part of what he calls the jazz mindset – like when jazz musicians seek out playing situations that are “over their heads” to stretch themselves and play in challenging contexts. The learning theorist Jack Mezirow called these experiences disorienting dilemmas and I guess, for a jet pilot, loosing both engines within moments of takeoff would be the mother of all disorienting dilemmas.

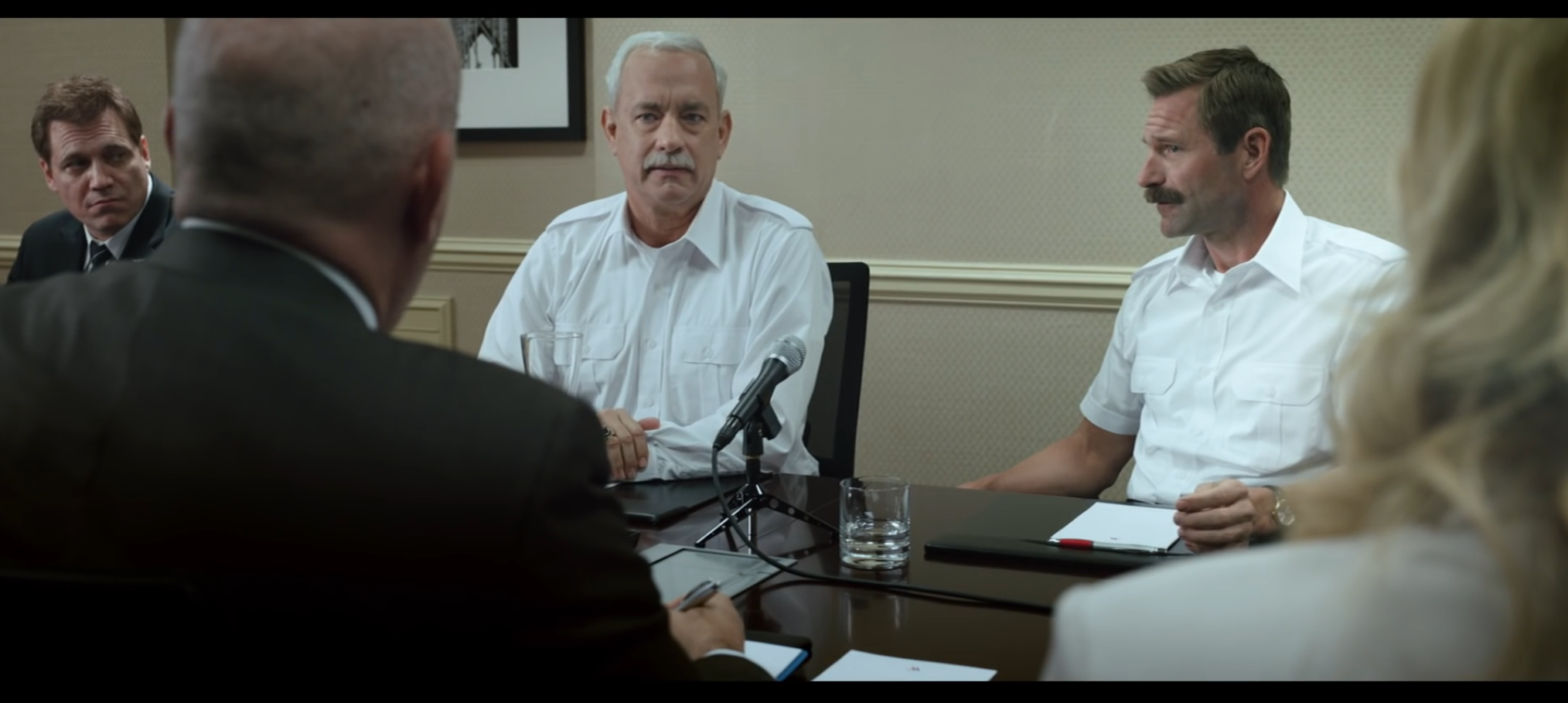

There is one key scene in the movie “Sully” that breaks down Sully’s thoughts and actions during the actual event. Here it is with a side-by-side interpretation of how these thoughts and actions correspond to the theories found in Mezirow’s learning stages and Barrett’s jazz mindset.

| SCRIPT Examiner #1: Today we begin with our operation in human performance investigation on the crash of US Airways flight #1549. | LEARNING STAGE/MINDSET Assumed, unquestioned, familiar routine |

| SCRIPT Sully (interrupting): Water landing. | LEARNING STAGE/MINDSET Being open to alternative perspectives (Mezirow) Provocative competence (Barrett) |

| Examiner #1: Captain? |

| SCRIPT Sully: This was not a crash. It wasn’t a ditching. We knew what we were trying to execute here. It’s not a crash. It was a forced water landing. | LEARNING STAGE/MINDSET Exploring alternative perspectives (Mezirow) Affirmative mindset (Barrett) |

| Examiner #2: Why didn’t you attempt to return to LaGuardia? | Disorienting Dilemma (Mezirow) |

| Sully: There simply was not enough altitude. The Hudson was the only place that was long enough and smooth enough and wide enough to even attempt to land the airplane safely. | Maximizing Diversity of Alternatives (Barrett) Affirmative Mindset (belief that a solution exists and that something positive will emerge- Barrett) |

| SCRIPT Examiner #2: Air traffic testified that you stated you were returning to LaGuardia, but you did not. | LEARNING STAGE/MINDSET Assumed routine. |

| Sully: I realized I couldn’t make it back, and it would have eliminated all the other options. Returning to LaGuardia would have been a mistake. | Revising assumptions (Mezirow) Using errors as a source of learning (Barrett) |

| Examiner #1: Okay. Let’s get into how you calculated all those parameters. | … |

| SCRIPT Sully: There was no time for calculating. I had to rely upon my experience in managing the altitude and speed of thousands of flights over four decades. | LEARNING STAGE/MINDSET Minimal structures that allow maximum flexibility (Barrett) (Accessing Tacit Knowledge) |

| Examiner #1: You’re saying you didn’t do any… | …. |

| Sully (interrupting); I eye-balled it. | Leap in, Take Action (Barrett) Acting on revised assumptions and perspectives (Mezirow) |

| Examiner #1: you eye-balled it. (Examiner #2 grimaces and looks down) | |

| Sully: Yeah. The best chance those passengers had was on that river and I’d bet my life on it. In fact, I did. And I would do it again. |

The extraordinary integrative thinking that Sully demonstrates is a skillful combination of formal education, technical training and tacit knowledge. And, as he points out, the tacit knowledge involves thousands of hours of practice. It also involves a concurrent, and iterative cycling of challenging and revising assumptions in real time — and creative thinking — seeing alternatives others don’t, like landing on the Hudson River.

No one, including Sully, would ever plan to land a jet on the Hudson River. He did it because, in the midst of great uncertainty, it was his only alternative, and an alternative that only he saw. Sully demonstrated what Barrett calls an affirmative mindset – he believed it could be done. He drew upon his dynamic capabilities, was emboldened by the elimination of all other alternatives and committed himself to a full execution of the intended action. It became his purpose – to survive.

The scene can be viewed on YouTube here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6iJ1QkHD5TY